John Johansen’s Restless Spirit

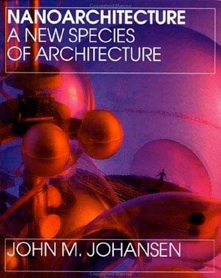

by Kevin C. Lippert from NANOARCHITECTURE: A New Species of Architecture by John M Johansen, published by Princeton Architectural Press

On first meeting, John Johansen is an unlikely prophet of a new millennial architecture based on the latest revolutions in science and technology. [Approaching his 95th year] it seems a more propitious moment for him to bask in the current admiring rediscovery of ...many elegant houses he built in the 1950s, than to be taking to the pulpit of experimental design based on nanotechnology, bioengineering, magnetic levitation, self-regulating structures, composite materials, and other developments more likely to be found in the pages of Popular Mechanics than the newsletter of do.co.mo.mo. It's a surprising twist for [a nonagenarian] and former outspoken defender of the high-modern faith.

But the career of John MacLean Johansen, born 1916, the son of two successful New York studio painters, has been nothing if not full of surprising twists and turns. A 1942 graduate of Walter Gropius' Bauhaus-in-Boston, Harvard Graduate School of Design, Johansen began his career at the apogee of American modernism. However, unlike most of his classmates, including Paul Rudolph, Philip Johnson, Edward Larrabee Barnes, and I.M. Pei, Johansen's dedication to the modernist gospel was not deep-seated, and even early on he proved himself a restless experimenter. In truth, alternative voices were never entirely exiled from Harvard: Le Corbusier was a frequent visitor, and the venerable Frank Lloyd Wright urged students in his lectures-from which faculty were excluded-to "leave Harvard immediately" before they were corrupted. The influence of Alvar Aalto's organic romanticism could also be felt moving up the Charles River from MIT.

The young Johansen was attracted to it all: in a kind of Borgesian catalogue he lists as early influences Wright, the "haunting austerity" of Gropius (who was to become his father-in-law), the "humble, almost childlike innocence" of Marcel Breuer, and the sculptural elementality of Le Corbusier's Ronchamp. To this list he later added: the thin-shell structures of Felix Candela and Pier Luigi Nervi, the strut construction of Buckminster Fuller, the rationalism of Mies van der Rohe's steel frames, Andreas Palladio, Carl Jung's theory of archetypes, Gaston Bachelard's Poetics of Space, Italian Renaissance painting, systems theory, Japanese Metabolism, chaos theory, and more. Throughout his career, Johansen has been a kind of architectural omnivore, always fascinated by the stylistic, intellectual, and technological currents that have swirled around him.

Harvard Five

In spite of his wide-ranging interests, Johansen's earliest works were nonetheless straightforward postwar modernism. After Johansen graduated from Harvard he spent the remaining war years building woodframe Navy barracks and subsequently working as a researcher for the National Housing Agency. After the war, he was employed briefly as a draftsman for Breuer, and joined Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, where he worked "on loan" on the United Nations project under Wallace Harrison. In 1948 Johansen moved to New Canaan, Connecticut, where several other Harvard colleagues - including Breuer, Johnson, Eliot Noyes, and Landis Gores - were already encamped. This loose-knit circle, more social than professional, came to be known as "The Harvard Five."

Neo-Palladian phase

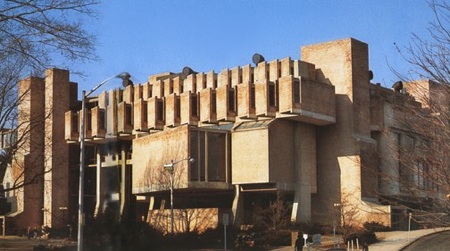

Over the next ten years, Johansen built a series of elegant modern houses typical of the period. Johansen calls this his "Neo-Palladian" phase. Certainly the possibility of European travel after World War II provided a source of inspiration and delight for Johansen and his peers, especially given the antihistoricist stance at Harvard. Johansen wrote in Architectural Forum in late 1955 of "a new interest in the architecture of the past," and of the "timeless importance" of the abstract qualities of space and mass that he found in the Italian Renaissance-qualities hardly inconsistent with the kind of "domesticated" Yankee modernism already pioneered by Gropius and Breuer, and under further development in the hands of Johnson, Rudolph, and others.

The houses of this period - like the Goodyear House of 1955 and the Villa Ponte or Warner House of 1957 - were formally inventive, engaged their sites in clever ways (Villa Ponte literally bridged a stream), made use of luxurious materials, and were accomplished in their knowledge of the stylistic and tectonic developments of their day. They were also well received - the Warner House was a Record house in 1958 - and Johansen's residential practice flourished.

biomorphic liberation

Johansen found the simplicity, balance, and order of these Neo-Palladian designs "exhilarating," so it makes the out-of-Ieft-field appearance of his "Spray-Form" projects thin-shelled concrete structures - that resemble nothing if not flowers - that much more startling. Commissioned by the American Concrete Association as part of an ongoing series of demonstration projects, the British critic Reyner Banham hailed them as symbolic of a conversion to the religion of technology; Johansen remembers them more as an effort to distance himself from "the modern box" as well as experiments symptomatic of his "insistent spirit of investigation."

Spray House #2 of 1955 typifies these projects. Intended as a residence for Johansen and his family, the house was framed by steel rods bent into shell-like shapes that were fastened together at a central point. These rods were then covered with smaller rods, and again with paperbacked steel mesh. Concrete was to be sprayed directly onto the armature, making a rigid shell approximately 8 inches thick; the resulting shell was to be coated outside with plastic for waterproofing, and inside with sprayed insulation and paint. Clear plastic would fill gaps between the shapes to create windows. Floors, walls, and ceiling would form one continuously smooth surface, like the inside of a seashell. Radiant heating coils would be embedded in the walls; furniture, steps, and shelves were similarly to be incorporated into the structure itself. The great advantage of this construction process was that no formwork was required, resulting in both more organic forms than traditional poured concrete would allow, as well as lower cost.

Although "gunite" - sprayed concrete - was invented in 1907 by Carl Ethan Akeley, who needed a way to spray aggregate onto mesh to build dinosaur models, the technology was, and is, more commonly used for building swimming pools. Le Corbusier used it at Ronchamp (1950-55) with an effect on the architectural world as electric as Frank Gehry's Bilbao Guggenheim today, and was most likely the inspiration for Johansen's explorations in crustacean forms. It is also likely that Johansen was aware of the highly publicized thin-shell structures of Felix Candela and the ferro-cimento structures of Pier Luigi Nervi. Whatever its origin, the biomorphic appears as a liberation for Johansen, and, although Spray House #2 was never built, he used the idea for a series of projects that followed in rapid succession, including the United States Trade Pavilion at the International World's Fair in Zagreb (1956), a church in Norwich, Connecticut (1957), and a restaurant and motel compound in Mt. Kisco, New York (1957). It seems likely that his spray-form houses influenced the architect/artist Frederick Kiesler, who developed a series of versions of his own "Endless House," a similar biomorphic shell structure. Palladio, Carl Jung's theory of archetypes, Gaston Bachelard's Poetics of Space, Italian Renaissance painting, systems theory, Japanese Metabolism, chaos theory, and more. Throughout his career, Johansen has been a kind of architectural omnivore, always fascinated by the stylistic, intellectual, and technological currents that have swirled around him.

Johansen succeeded in having one of his shell projects built: the Zagreb Trade Pavilion. It was not, however, a happy experience: Johansen complained that the Yugoslav concrete, and workers, were of low quality, and the structure consequently required secondary support. Whatever the failings of the project, it did attract attention in Europe: in London, the Archigram group went so far as to label Johansen's "stomach-like" shapes "Bowellism, "For the boys in Archigram," wrote Archigram member Michael Webb, "(Johansen) was our genuine American hero: each successive project a radical departure not only from conventional practice, but even from his own previous oeuvre.”