John Johansen's Present Tense

by Lebbeus Woods from John M Johansen: A Life in the Continuum of Modern Architecture

by John M Johansen, published by l'Arca Edizioni

John Johansen's Present Tense

by Lebbeus Woods from John M Johansen: A Life in the Continuum of Modern Architecture

by John M Johansen, published by l'Arca Edizioni

LEBBEUS WOODS COMMENTARY

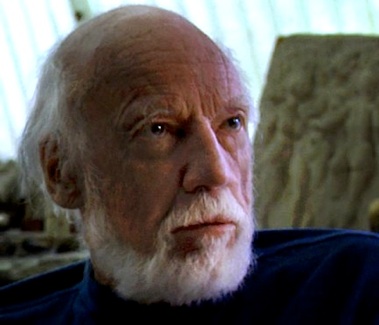

From the beginning, John Johansen has been an iconoclast and a fighter for architecture as he saw it, as he believed it could be, given the right mix of intelligence and daring. For forty years, he has maintained the right mix to a remarkably high degree, realizing many good buildings and a few great ones, a record that most architects would envy.

Today he is teacher, writer, and thinker with many things to say to the coming generation of architects, not only from his own long experience as an architect, but from a clear vision of what architecture might yet become. He is, more than ever before, an experimental architect whose projects explore concepts of form, space, structure and materials expressing ideas shaping society and culture.

Much current discourse in architecture is concerned with the role of theory in practice. This is an understandable shift off focus away from the exigencies of building, not only because there is a momentary lull in construction, but more so because the field of architecture itself is undergoing deep structural changes in response to even deeper changes in the structure of contemporary society. New foundations for the practice of architecture are now being created, those which will support a broader definition of architecture's limits and limitations than has existed before. As an architect who is concerned with ideas that influence buildings, Johansen participates in the present conceptual reformation.

The impact of media has opened the question of what is "real" and what is "virtual," not only in the academic world, but in the media itself, exposing to the public an epistemological crisis that has been simmering throughout most of this century, and seems close to a boiling point. To "deconstruct" something has become a part of everyday parlance and, while it is used in most cases differently than its author intended, the ubiquitous presence of the term signals a self-consciousness that is fundamental to a radical shift in the nature of knowledge now widely underway. Boundaries between concepts of subjective and objective knowledge have long become blurred in the sciences, and are now becoming so in almost every phase of public life. News magazines, for one example, are no longer structured visually to differentiate between hard (objective) news, (ambivalent) advertisements, and (subjective) opinions, but have become indeterminate visual and informational fields, requiring close and highly personal readings, if any sense at all is to be made of them. Television... with its surfeit of almost indistinguishable options, is the precursor of such indeterminacies in all aspects of contemporary life.

epistemological shift for architecture

The meaning of this epistemological shift for architecture is not only that building may no longer be limited to the placement of concrete, steel and glass in a manner somehow appropriate for human habitation, but also that--even when it is limited to this traditional definition--it will no longer be sufficient, or even possible, to create an objectively determined, purely abstract construction of universally understood purpose or meaning. The goal of early Modernism, which identified itself with classical precepts of cause-effect, subject-object relationships, is therefore unattainable today.

Modernism, in its epistemology, was a new form of classicism thrown over an increasingly unclassical, unstable industrial society. What stands in place of these now outmoded concepts for design and building is something close to what has been called "expressionism," but which is more accurately to be understood as a dialogical relationship, a conversive interaction between architect-as-human-being and inhabitant-as-human-being. Exactly what is meant by "human being" emerges from the precise contents of the dialogue, and not by any abstract structure of meaning. All that is certain is that stereotypes and - to use a more academic term - typologies of person, place and event are no longer valid premises for the conception or making of architecture. To be an architect now means to be a human being first, to have a persona, a distinctly individual life of the mind and of the body, in order to enter into an ethical relationship with others who, by necessity or desire, have equally distinctive existences. In all these regards, and particularly the last, Johansen has been exemplary. Being one of those who is breaking down in architecture the now-artificial boundaries between subjective and objective, between the virtual and the real, his thinking today is at once self and other-reflective.

THE NEW ETHIC

In his lectures and commentaries on "The New Modernity" and "The New Ethic;' Johansen speaks of a new perception that reveals an organic wholeness and inseparableness of the world, rather than the fragmentation presented by older, mechanistic views that recognized a world of diverse parts that were interdependent, but always, to some degree, interchangeable, hence merely typical. At the same time, a paradoxical condition is created. Each part, while inseparable from the whole, is unique to the conditions that surround and support it. Experience is, therefore, always unique. The indivisibility of the world amid the uniqueness of its parts is exactly the view presented by quantum theory, later extended into cybernetics and systems theory, and refers to the unity of observer and observed, of perception and reality. It is also the view offered by current theories of "chaos," or extremely complex, nonlinear systems of order, which only became possible with the advent of analog and digital computers, superseding the linear mathematics of differential calculus. Concepts of the "butterfly effect," feedback mechanisms, circularity and recursive systems were the result of the epistemological revolution that in turn made electronic technology possible. Johansen had introduced some of these ideas into architecture, and incorporated them into several buildings, at the very moment when the electronic revolution was beginning to make its impact on society-at-Iarge.

ESCAPING establishment modern

In an important 1966 article, Johansen writes: Now a way of escaping from the habits of "establishment modern" ... is by feeding off cultural and technical situations in other fields of more advanced development. For me the choice of another field is advanced electronics. The temptation in this process would be to merely imitate forms seen in electronic devices, i.e., "techno-aesthetics." However, the adoption of organizational systems, if adapted to particular human services, can indeed be valuable. Furthermore, borrowing from the terminology of other technologies can also be helpful in forming, for architects, new channels of thought.

By the shift from an art-historical mode of thinking, which had dominated modern architecture, Johansen was able to liberate his conception of architecture in a way that was synchronous with the profound epistemological changes then beginning to transform the structure of society, and thus the meaning of architecture itself.

inspired by technology and science

At the same time, other architects were also seeking ways to escape the bonds of doctrinaire modernism, drawing on "other fields of more advanced development." Robert Venturi chose the path towards liberation of reinterpreting history in semiological terms, seeing architecture and the urban landscape as a language of visual signs. This was an exceptionally influential direction, especially in the United States, where commercial pragmatism had, in fact, already realized his vision.7 He, and those architects who followed him, found a ready-made context of popular iconography into which they could place more esoteric works that acquired immediate meaning, particularly in the atmosphere of the populist sixties and post-Watergate seventies. Peter Eisenman, by the middle seventies, introduced his own architectural interpretations of then influential developments in linguistics, taken primarily from post-Structuralist, essentially anthropological and cultural theories. Johansen's approach, inspired by technology and science, differed radically from these, although it shared the same epistemological roots, planted in a new ambiguity, a new uncertainty and indeterminacy.

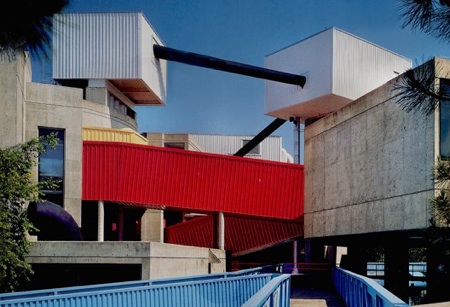

In the Mummers Theater project, which he began to design in 1965, and which was constructed in Oklahoma City by 1969, Johansen realized his ideal of a new, paradoxical architecture. Knowing that the old, static methods of creating a satisfying architectural composition were of no use in a rapidly changing society, he created an armature, an "ordering device;' on which human activities, and thoughts, could organize themselves.

"The future city," he wrote, "may look like one building .... the building, as a fragment, may look like many. Except for scale, the governing principle will be the same." The principle, of course, was the indeterminacy of meanings, values, experiences, and forms.

Neither the Mummers Theater, nor the Smith Elementary School, completed in Columbus, Indiana in 1970, are functional buildings in the modernist sense of the term. They do not posit space and sequences of space according to a fixed program of use, determined in advance, even though they fulfilled successfully the programs originally given to the architect. These buildings go far beyond functionalism as defined by the meeting of requirements, the solving of problems, the satisfaction of needs. They are not buildings at all, in the commonly understood sense, but spatial matrices, lattices of possibilities. And yet they are not infinite lattices or possibilities.

merging of the virtual and the reaL

Instead, they are finite, bounded by the particularity, the idiosyncrasy of their arrangement, embodying only specific thoughts and actions at a given moment. It is not by chance that the opportunity to design both of these building types in tandem gave Johansen the liberty to fulfill his own experimental program for architecture within the given and buildable contexts. This fact confirms the new epistemology: the place of learning (school) and the place for the invention of other realities (theater) today share a common purpose, and even a mutual interdependence as regards technical means and conceptual goals. And it suggests a further, perhaps less obvious condition: that in the electronic, information age-the age of the merging of the virtual and the real, the subject and object-every place of living and place of work has become a place of learning in the new, dialogical sense, a place whose primary function is the invention of personal and social realities.

The Mummers Theater was met, at the time of its completion, with a kind of excited disbelief. Johansen's own assessment prompted others: "It is the surprise, unexpected juxtaposition, superimposition, crowding, segregation and confrontation of elements which accommodate the human functions and movement patterns, which give the architectural vitality the building really has."

"At this extreme," Arthur Drexler wrote, "the idea of composition itself is called into question ... yet elements of what is meant to look unorganized are finally perceived as having their own order.” From the beginning, it was recognized that this building brought something entirely new into architecture, something disturbing, yet much-needed: an almost primitive energy that attacks the world of learned structure, but only in order to create another type of structure, pushing up from deep beneath.

IMPROVISATION AND HUMOR

Johansen himself writes: “...I was weary of pretentiousness, perfection, and eloquence in the work of most contemporary architects, and as a means of mocking them, I adopted the humble virtues of improvisation, economy of means, direct solutions, even humor. ‘Adhocism’ may be said to describe this attitude and approach. It deals with immediacy, the here and now, with what most effective course of action can be taken without deliberation or idealistic notions of perfection.”

The tentative and precarious composition of masses Johansen devised for the Mummers Theater seems to arrest their movement in time. It is not a random composition of forms, hardly a composition at all. Instead, what is offered by the architecture is a moment of poise, a dynamic balance, a transition, an arbitrary decision of life, and-not incidentally-of the life of theater.

Some years later, Michael Sorkin, the estimable critic, called the Mummers Theater "a bubble diagram come to life," astutely referring to the freezing of a pattern of activity that an architect might have sketched in an early phase of design. This comment, however, also dates the project in an unfortunate way, placing it within an archetypally modernist "functionalism" to which it does not belong.

For not only does the building call into question the idea of composition, but also of function and predetermined program. he disparate assemblage of masses, with their peculiar, almost surreal, connectors of bridges and tubes, does not evoke any particular human use, but instead a kind of anti-use, an "antiarchitecture," as Johansen himself has called it, a resistance to the very idea of usefulness or utIlity. There is something severe and alien in this building which seems to challenge notions of comfort and security, and demand inhabitation that, by virtue of its unfamiliar dimensions, cannot be predicted or devised from former, more normative conditions.

The architect has here become a provocateur, an active participant in a theater of existence. The architecture of the Mummers Theater is a gauntlet, thrown at the feet of those who claim to invent life from "the stuff that dreams are made of." What it asks for in response to its highly idiosyncratic forms and pattern of space is action by others of an equivalently inventive potency.

The Smith Elementary School of this period met with the same curious praise from contemporary commentators. "Johansen more or less lets things happen in design ... the building suggests a quality which he describes variably as 'happy, quick, out of the catalogue, direct, honest, and occasionally naughty." The echoes of modernist building ethics-integrity of function, structure and materials ring through such statements, but they do not reflect Johansen's own, more astute confession. "My purpose in both these buildings, Mummers and Columbus, was to excite, intrigue, tempt and involve those who attempt to approach."

Given the laws of compulsory education that bring children to elementary schools in the United States, his ideas and the architectural realities they lead to are almost quantum mechanical by comparison. They invoke a latent potentiality in human experience, within a precise range of physical and intellectual conditions. They encourage its realization through a presumption that people-teachers and students-have choices, but these can only be "attempted" if they are made explicit in the physical world people inhabit, and if people accept personal responsibility for them. Johansen's design embodies a new paradigm of education: the asking of questions for which the answers are not known in advance.

RADICAL ALTERNATIVE TO TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE

These two projects offer a radical alternative to traditional architectural thinking and design. Instead of confirming the normative, they set out on a new course altogether, one that can only confirm the idiosyncratic and the individual, recalling the Transcendentalist attitudes of Emerson and Thoreau and the "open road" of Whitman. In this sense, it is idealistic and characteristically American.

It is worth noting how much these designs differ from the Plug-In City proposed by Peter Cook in the early sixties, the modular systems of the Metabolists, or the Fun Palace project of Cedric Price of the same periodwork which Johansen frankly recognizes as an inspiration for his own. Unlike these former projects, the applications of advanced technologies in the Mummers Theater and the Smith Elementary School are more conceptual than formal, more epistemological than pragmatic. The result is that the buildings-unlike their European counterparts, such as the Centre Pompidou-hardly seem technological at all. They appear as primeval, visceral constructions, willful, complex, even arbitrary, as though belonging to an aboriginal world-an Urwelt-struggling only now to be born. Their tremendous originality resides at once in their conceptual clarity and formal ambiguity, the right mix of intelligence and daring for the information age just dawning at the moment oftheir completion. They incorporate Archigram's serious playfulness, and are obvious precedents for Frank Gehry's juggled masses and his iconic use of commonplace materials, as well as the antic geometries of Coop Himmelblau. They were a fuse lit to the deconstructionist explosives that did not shake the architectural world until more than ten years later. And they are precursors of Johansen's own most recent and conceptually important projects. These two rough-hewn masterworks emerged from more than twenty years of architectural practice.

Like Louis Kahn, Johansen has had a long gestation. And like Antonio Sant'Elia, his oeuvre sometimes offers a curious contrast between brilliant inventiveness and skillful digressions. It should never be forgotten that, in one crucial way, John Johansen is an architect in the traditional sense: his impulse is always to realize his ideas, impulses and desires in building. Theory and philosophy are for him a means to an architecture in which he can passionately believe, and then can dispassionately forget, when a more challenging idea comes to him. Mies van der Rohe claimed the same prerogative, but found one idea commanding enough to sustain him throughout his life. Johansen is a man of a different epoch than Mies and the other modern architects he calls "the giants." His has been an epoch in which their great ideas were realized and part of a mythic past that was already showing signs of wear in the late-forties and fifties. The first signs of disillusionment with modernist principles in particular, and commanding ideas in general, amounted to the pre-dawn of a postModern age that would not occur in architecture until the giants passed, and their authority had been broken. In the meantime, Johansen and others-Saarinen, Stone, and Rudolph among them-began to develop their individual directions.

A history of architecture could be written about modern architects' struggles with "the box." Frank Lloyd Wright opened the century with an eloquent polemic against the boxy Victorian house, then created his dynamic prairie houses, with their overlapping, interpenetrating spatial volumes. Mies, variously under the influence of Wright and Expressionist ideas and forms, liberated himself from the box in some early house and office building designs, but after the seminally anti-box Barcelona Pavilion returned to the box with a vengeance, turning his interest to subtle modulations within its "universal space." Le Corbusier was a sculptor from the beginning, carving and stretching the box sometimes beyond recognition, but always in earnest dialogue with it.

DECONSTRUCTING THE BOX

The post-Modernists, following Venturi's lead, were content to “decorate the box." The Deconstructivists exploded it. So it has gone, and will continue to go. These struggles, capitulations and recapitulations are not only the stuff of fashion. They are confrontations with a dominant form of knowledge that are necessary if that form begins to fail in its representation of the world of experience. Johansen's earliest designs for houses were self-conscious efforts to break not only the form of the box, but also its authority in architecture, its grip on people's minds and imaginations. He had read Sigfried Giedion's Space, Time and Architecture, which tried to bring Einstein's relativity theories into a new critical discourse on architecture, but was not ready himself to draw directly from other fields of more advanced knowledge. So he turned, as many had before him, to architectural history.

NEO-PALLADIAN

Any form of literal historicism, particularly any form of ornamentation or decoration, had become anathema for modern architecture, even though its masters, such as Mies, often relied on classicist principles of organization and form. Nonetheless, for Johansen's generation, historicism became the forbidden fruit that tempted them. Because he was a student of Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus and modern architecture's most famous teacher, the fruit seemed all the sweeter, too sweet to resist. He called his first built designs for houses “neo- Palladian," giving them romantically provocative names, Villa Grotto, Villa Croce, Villa Ponte. They are distinguished more by ingenious interactions with their mostly exurb an sites and inventive handling of materials--in other words, characteristics that Gropius might have admired--than by the sorts of historical allusions that, twenty years later, would produce a more literal historicism. Perhaps aware of this, Johansen began to dig deeper into history, exposing older and older layers.

DUBLIN EMBASSY

In his Dublin Embassy building, Celtic and Druidic stone circles are an obvious point of reference. It is as if some instinct within him wanted to reinvent architecture, and to begin at the beginning. The precast structural enclosure wall did not resemble a stone circle, however, but more a filigreed piece of stone jewelry, a wedding ring evoking mythic rites and pagan meanings. Johansen was on to something. The world of elemental concepts, which he would later find in electronics and physics, emerged at first from outside any sanctioned history of architecture, providing conceptual elements for an idiosyncratic Urwelt. At a lecture in the mid-eighties in New York that was in part directed against postModernism, he spoke from the audience. The problem with the post-Modernists, as he saw it, was that they didn't go back far enough into history!

AN ARCHITECT OF FORM

Very often, it seems that John Johansen is an architect of form rather than space. This is not to denigrate the interior spaces of his buildings, for they are usually intriguing and full of surprises. Yet they are clearly the product of form, not its generators. The most vital spaces that Johansen's buildings create are external ones, in the sense that their clear and articulated masses generate an extremely dynamic surrounding space, The same cannot be said of every architect's work. Johansen's buildings are like vortices, spiraling space inward and at the same time spinning it back out.

Considering the nature of the ideas informing his work, it is not surprising that Johansen is instinctively drawn to the creation of exterior space, which belongs more to the domain of the world-at-Iarge, More hermetic souls, such as Wright, who chose to live in the wilds of Wisconsin and Arizona, are essentially philosophical, self-reflective, introspective, inner-spatial. Wright's buildings are created from the inside out, If philosophy is the love of knowledge for its own sake, then Johansen is not philosophical by nature, but involved more in the relationship between ideas and culture, He is interested more in how the world works than in what it means, or what its essence is, its inner and concealed place of origin, Accordingly, his buildings seem to be created from the outside in.

LIBRARY AS AN ELEVATED BOX

A perfect example of this aspect of his work is the Goddard Library, completed at Clark University in 1968, Designed just prior to the Mummers Theater, this extraordinary building has some of its formal energy and vitality, but is different in fundamental ways. The comments of a critic, writing at the time of the publication of Johansen's design drawings and models for the library are very much on the mark: “The core of the Clark library is an elevated box in which books are stacked. The perimeter, however, is a seemingly random collection of shapes and angles that makes the irregular elevations of the Goddard Library make the contemporary City Hall of Boston look positively Miesian.”

The connection noted between the library and another building inspired by Le Corbusier's influential design for the monastery at La Tourette confirms the mainstream Johansen was working in. But, more importantly, the contrast is made between the bland core of the building and its exciting "perimeter:" its exterior presence and space. The interior space is a ‘box' the very form that Johansen had earlier been determined to break, which he in fact had broken in earlier projects, and most dramatically in his Mummers Theater and Smith Elementary School designs. The exterior, however, is an exciting and complex melange of forms. La Tourette-like or not, that breaks the box in all directions, generating a visually kinetic exterior space. The Goddard Library conceals the functional box of books tacks, or buries it in the complex forms of contemporary cultural life. In this sense, the building's exterior is a library, too, clasping the ordered language of the past in the diverse and asystematic language of the present.

Johansen himself, for all his intuitiveness, is and was aware of the epistemological roots and effects of his design. Referring to it as "a building not of the passing mechanical age, but of the electronic age” he describes the exterior as being "like the rear, not the tidy front, of a Xerox copier, with the components and their connections rigged on a structural chassis and exposed." With this statement he reveals one of the most difficult questions confronting architecture in the age of electronics and information: how to express in visual terms qualities which are not visual. Does the architect do so through symbolism, or through a kind of imitation of electronic parts, or by analogous means, that is, by rearranging the structures of previously understood architectural order until they evoke a new kind of order, a kind of non-sense that is analogous to the non-visual order of information exchange and electronic communications? In the library he takes the latter course. It is "like" an electronic machine-in his own words, "anti-perfection, anti-masterwork, anti-academic" - not at all in appearance, but in idea. John Johansen's bête noire has been post - Modernism. His work and career were not threatened by rival theorizing, but were no doubt stimulated by it. However, the popularity of literal historical allusions, of an ironical pastiche of styles, developed by Michael Graves and Robert Stern, Charles Moore, Philip Johnson and others, which played so successfully with conservative developers and the public, undercut the more difficult position Johansen had worked hard to establish through the sixties and seventies. Because he considered building as the final and ultimately only acceptable test of architectural thought and design, the fact that commissions for major projects gradually diminished for him, as it did during this same period for his like-minded peers Breuer, Pei and Rudolph, was keenly disappointing.

A RETURN TO THE EXPERIMENTAL

The shrinking of Johansen's professional practice, however, eventually led to a new period of inquiry and inventiveness. Returning to his experimental mood of the fifties, when the rough outlines of a new architecture first began to take shape, he has proposed a series of projects whose very titles reveal his ambition to push harder than ever at the limits of architecture, as even he had previously conceived it.

Working under the overarching thought of a "poetics of technology;' Johansen coalesces new forms of knowledge, developed in the sciences and manifest in everyday life through new technologies, in the conception and making of architecture. His projects embody the psychological and sociological cohesiveness inherent in architecture's collaborative nature, relying at the most basic level on the individual character and vision of the architect. Only an architect possessing a strong individuality can appreciate it in others, and, through innovative designs, make physical conditions that are liberating for others.

All of the most recent projects are technological in character. They proclaim the essential benevolence of technology, or at least its potential for human and environmental good. This is in contrast with the mainstream of post-Modernist thought, which can no longer see, as the modernists did, technology as the foundation upon which a truly modern consciousness could be constructed. To many thinkers and architects today, advanced technologies seem a threat to both the human and the natural, and are viewed with suspicion. Mass electronic media are in the control of large business interests and government, and seem to serve only their narrow and short-term goals by enforcing a conformity of opinions and desires. Industrial technology is the captive of consumerism, whatever the costs to the environment. Both advanced industrial and electronic technologies have been dominated by the military, with its ambiguous ethics with respect to both culture and nature, and its sometimes disastrous effect on both.

Johansen, in the face of this, insists on turning technology around, of making it both a positive factor in contemporary life and a foundation for the future. His lifelong contacts with physicists, engineers, environmental experts, anyone who can help in his understanding of the crucial issues to be addressed, demonstrates his determination in finding the architectural means to realize entirely new kinds of technological projects.

a search for poetry

The difference between Johansen and other technologically-oriented architects is his lack of interest in stylistic and formalistic issues, and at the same time a search for "poetry." This seeming contradiction recalls his Mummers Theater and Smith Elementary School projects, in that the poetical exists in the idea and form of an indeterminate network of parts that are nevertheless indivisible as an experiential whole. Johansen is interested primarily in performance, understood not only in the quantitative, technocratic sense, but in the theatrical and the existential. It is the human performance that brings coherence to the architectural form, not the other way around. Performance is not itself something determined in advance, but varies with people's desires, needs, expectations, perceptions. Architecture can control people by rigid symmetricality and martial order, or it can liberate people's natural spontaneity by structuring space ambiguously, playfully. Johansen sees the present society as one in which play is more important than control, in which increasing the number of choices is more important that imposing predetermined limits on thought, action and experience.

As the number of choices available within a network increase, play becomes more important; formal rules of thinking and behavior are overwhelmed by the dynamics of complex and changing conditions - a description suitable for society in an advanced technological and information age.

Johansen's later projects are games in space and time, playful epiphanies of invention and spontaneity, meant to provoke and stimulate others inhabiting such an age, as well as himself. A succession of projects in the late eighties continues Johansen's earlier explorations of industrial technologies and the ways they might affect architecture and its potential for provoking new experiences and possibilities.

INTELLIGENT TECHNOLOGIES

The Froth of Bubbles, Suspended Web and Space Labyrinth projects share the architectural concept of a structural armature into which is woven a network of forms and spaces, animated by various computer-controlled pneumatic and electro- mechanical systems. These projects are refinements of the more elemental and abstract Mummers and Smith Elementary School projects, by the tectonics are more articulated, fragmentary, diverse, and the technologies more "intelligent;' self-regulating and responsive. While lacking the visual strength and viscera power of these earlier masterworks, they are conceptually more adventurous.

But in the more visually potent Metamorphic Capsule project, Johansen moves from the familiar building vocabulary of industrial technology directly into the fluid-dynamic world of electronic technology, giving the advanced concept of "cyberspace" new architectural images. The space formed for inhabitation is no longer designed according to traditional standards. Instead, its form emerges from the shifting potentials of a computer program, indeterminate in the old sense of having been predicted by the architect through the making of models and drawings. Resembling more a fluid bubble than a building, the space for habitation continually changes its configuration, according to parameters that are not clarified by any brief for inhabitation. The architect, still invoking functionalist norms, concedes that: ... this project, if actually built, offers little utilitarian function. However, as a simulation chamber, a mood room, a theatrical, scenic envelope for a contemplative, meditative or inspirational experience, it may have a useful service.

The principal virtue of the projected space is precisely that it has no "utilitarian function," that it offers a potential that can only be defined as "metamorphic." The metamorphosis of what? Even given the faint stabs at justifiable functions, the simulation, contemplation, or meditation of what? It is to Johansen's great credit that he goes no further, but prefers to leave an open space in front of him, an empty horizon of meaning. With this project, he enters the terrifying, but humanistic domain of a freer future. Terrifying because the old touchstones of "function" and "utility"-those shibboleths of deterministic Judeo-Christian ethics-will be left behind. In their place will be "the new ethics." Their essence is performance, understood in the same way as the "theater/school" paradigm of the Mummers and Smith Elementary School projects, only now expanded to include kinetic characteristics of architecture itself. The Metamorphic Capsule is a cybernetic membrane, changing its shape according to shifting demands of human performance, becoming "a womb;' from which a new personal and social indeterminacy emerges.

Johansen seems ambivalent about this most radical of his projects. If he was at times in the past willing to "let things happen in design," he has now gone much further. The concept and design for a metamorphic womb signals the end of architecture as it has been known. Composition is gone, because the thing continually recomposes itself within an almost infinite range of possibilities. Function is gone, because it is unknown in advance. Structure-in the sense of a predictable order of form and space-is gone, because it is entirely fluid-dynamic, non-linear, even mathematically chaotic. All that remains is an intimate and unpredictable interaction between the inhabitant and the architecture. A new degree of human freedom is achieved, as a result of a new degree of human loss. Fixed ideas which have formerly given existence a structure of meaning have dissolved in a sea of uncertainties and unpredictables. Johansen resolves his doubts by suggesting that his project would be built within an existing fabric of cultural and spatial-temporal relationships, rich with the fixed points of reference people have always required for stability, sanity, survival. The metamorphic capsule is a special event in a context of normalcy.

ETHICS AND ARCHITECTURE

But if "the new ethics" are to be taken seriously, then their mandate for organic wholeness, networks as opposed to hierarchies, dynamics replacing statics, all lead to the metamorphic capsule as a new architectural paradigm. Both ethics and architecture continue to be shaped by the state of knowledge, and by the dominant concept of knowledge operating in society, whatever it might be. In the present society of increasing information exchange, less and less will be fixed in terms of the structure of anything. As this occurs, the fixed points of reference supplying meaning and stability will more and more be the facts of change itself, leaving transformation and metamorphosis not only as a way of living (which they have always been, but controlled in a rigid structure of "norms"), but as the structure itself. In that case, architecture-as all other forms of instrumentality-will eventually be subsumed by the continuity of existence.

It is the tendency of all advanced technology to become invisible. This is occurring today in two ways. The first is miniaturization, and the second, reformation of the organic. Miniaturization is the road from the vacuum tube to the microprocessor and beyond. Its aim is ever greater accessibility and mobility, thus ubiquity and universality. Somewhere along this road will be television implants in the brain or mechanical antibodies in the blood, the results of emergent nano-technologies. On the other hand, reformation of the organic involves the artificial manipulation of living things-plants, bacteria, animals, humans-by technological means. This is the domain of what is today called genetic engineering, but belongs to the wider realm of utopian aspirations that have always haunted the human psyche. Technology itself will disappear, but its effects will progressively, and perpetually, remain.

REFUSAL TO SPEAK IN IMPERATIVES

John Johansen's vision of a technological poetics in the Metamorphic Capsule project combines dialogically these two tendencies of technology. He infuses them with an elusiveness of meaning that invites not only poetic interpretation, but poetic participation by anyone who might come to inhabit a metamorphic architecture. He proposes an interactive architecture, in which people assume responsibility for their own actions, without impinging on the actions of others, confirming the cybernetic principle, "If you want to see, learn how to act." It is an affirmation of his belief that people have not only the abilities, but the need to shape to an ever-greater degree their own lives. He does not accept the argument that most people would not want or be able to take responsibility for their own conditions of living, that they need the hierarchies of meaning and purpose powerful social institutions have always imposed on urban space and form. For precisely this reason, Johansen refuses to speak in imperatives. He proceeds, instead, as an experimentalist, offering visions and techniques as the basis for a critique that the issues raised by his project demand. With the grace of a hard-won maturity, he has moved out from under the dread necessity to judge or be judged in absolute terms. He asserts, but does not insist.

PLIGHT OF THE EXPERIMENTAL ARCHITECT

John Johansen's long struggle to make architecture as he sees it, and as an instrument of life as he understands it, has gone through many stages, none of them entirely happy or ever easy. He, like Peter Cook, Louis Kahn or Buckminster Fuller - architects of otherwise quite different temperaments and work - has struggled through periods of both fame and neglect, never giving up the quest for realization of an elusive ideal. Architecture for such individuals is more than either a vocation or obsession. It is a way of living and thinking, a sensibility that informs the most intimate and fragile domains of the architect's own existence. Seen through an existentialist frame of experience, such strong and enduring personalities are important in a culture which nobly claims, as the present one does, to protect and nurture each individual human being.

Experimental architects must be able to accept the fact that they will sometimes fail outright, and at other times only realize part of the vision that drives them. Other architects and one can name many among those currently famous-find their style, and formula for design early, and spend their working lives refining what they already know. Johansen is driven by what he does not know and wants to learn through creative work. He understands that an experiment is by definition work in which intentions are clear, but the outcome cannot be known in advance.

EXPANDING ARCHITECTURE

Experimentation and the provisional nature of "truth" is in the great Western tradition of philosophy, art and science, but not architecture. The profession of architecture, because it is tied to capital and the public interest, clings zealously to its established truths, and discourages experimentation. Johansen and a few other architects have set out to expand architecture beyond a solid, or even inspired professionalism, into the wider domain of humanism. But such a goal demands a price: rejection by institutions that might become clients, but who do not believe in experimentation, except on their own terms--and the ignorance of professional colleagues who do not believe in experimentation because they are determined to defend the territory they have already conquered.

Also, the experimental architect will never produce a body of work that those who are looking for consistency above all else demand. In Johansen's case, his oeuvre is consistent in terms of quality of effort and result, but not so in terms of conceptual daring and innovation. His early period was one of intrepid explorations beyond the narrow limits of doctrinaire modernism. His middle period was one of more cautious professionalism, during which he channeled his innovative and rebellious spirit (with the exception of several brilliant outbursts of creative originality) into the architectural mainstream of the time, though with a panache that most of his contemporaries did not match. In his present period, he has become an originator and experimentalist, more daring than ever before.

His main appeal for the present generation will certainly be in the particulars of his present thought and work, their engagement with information-age technology and concepts, suffused with the passion and individuality of an architect who, after forty years of active practice, is still restlessly energetic and searching.

In many of the advanced schools of architecture today, students are asking questions about architecture that Johansen has been asking through his work for a long time, What role has architecture played in the lives of people and society, and how is it different today? Is architecture a form of knowledge, and in what way? Is architecture always to be defined in terms of construction and building, or might it also exist in other media? While the answers of the coming generation to these and other fundamental questions will certainly find forms different than Johansen's, his work and life are exemplary,

AN EMPHASIS ON IDEAS

His emphasis on ideas, rather than style, is an answer to the cynicism many feel today regarding architecture. While the style of a particular architect must certainly embody the ideas that drive his or her work, in a culture dominated by mass media, architectural styles can be separated from ideas and proliferate independently of them, becoming another quickly consumed "look." By asserting ideas, the architect makes this separation more difficult and at the same time emphasizes that ideas are shared by many and will naturally take many different forms, resulting in an exchange among individuals that is the only possible basis for a creative and just community. In the end, John Johansen's work is about community, and humanity, as much as architecture per se. His buildings, rooted in some of the most influential ideas of the present day, seem more than ever to point towards the creation of a new vernacular, a new fabric of space and time in which modern experience can increase, expand and deepen.

Website Copyright © 2011 John M Johansen All Rights Reserved

No information, photos, videos or audio on this website may be distributed, copied

or otherwise used without the written permission of John M Johansen or his representative

Website created by John Veltri and Marguerite Lorimer EarthAlive Communications www.earthalive.com

Please direct inquires to info@earthalive.com

Lebbeus Woods and Haresh Lalvani comment on John M Johansen as architectural innovator

BIOMORPHIC EXPERIMENTS

From this point of view, his “biomorphic" experiments are more interesting, and prophetic. The several buildings in this short-lived category, designed concurrently with the neo-Palladian houses, were never built, with the exception of a United States Pavilion at the World's Fair in Zagreb, Yugoslavia in 1956, which only partly realized Johansen's ideas. The term “biomorphic" refers to the conceptual origins of these sprayed, thin-shell concrete structures. Flowers and plants are literal models, as are the concepts of skins and other continuous, fibrous membranes. If architecture is to be reinvented, then perhaps it needs to return to nature altogether. But not quite. Nature does not interest him as much as the human. In caves and “troglodytic" structures, belonging to the most primordial beginnings of architecture, culture and society, he distances his thought from the puritanical presumptions underlying the modernist box. The “new ethics," for Johansen have always had to embrace a plasticity of space and experience, an exuberant hedonism and almost Dionysian sensuality that modernist doctrine denied.

Other architects in the fifties were beginning to use history as a source for design-Saarinen, Stone, Yamasaki, and Louis Kahn. But they used history in order to confirm its continuity in the present, and not, as Johansen did, to re-invent it. The sprayform concrete structures were his first designs without a respectable historical precedent. They no doubt influenced designs by other architects at the time, such as the TWA Terminal by Saarinen and foreshadowed Johansen's own visionary projects of the late eighties and early nineties.

John M Johansen in his 95th year:

Remembering the past, living In the present, designing for the future

Watch Video